N I G E L W E L L I N G S psychotherapist and author

Part One - Who's Who in the Great Perfection

Sri Simha

Yeshe Tsogyel

King Trisong Detsen

Padmasambhava

Ekajati

Rahula

Dorje Legpa

Mahakala

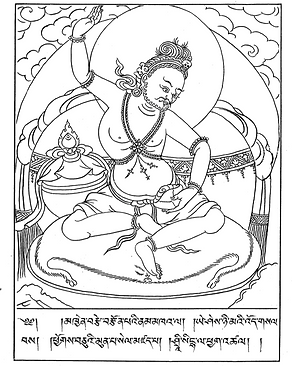

Sri Simha

Tradition has it that Sri Simha - the Lord of Lions - was the heart disciple of Manjushrimitra and the guru of Jnanasutra, Vimalamitra, Padmasambhava and Vairocana. As such he is absolutely central to the introduction of Dzogchen into Tibet. We have a number of different accounts of his life but they all represent him as a rather human and doubting student who is slow to take advantage of what is being offered to him. This is an abbreviation of his life story as told by Dudjom Rinpoche:

In the city of Shokyam in China, devout parents had a son who became the master Sri Simha. He initially studied the ordinary subjects such as logic and grammar with the Chinese master Haribhala and then at the age of twenty, when travelling to Suvarnadvipa in the west, he ...

Yeshe Tsogyel

Yeshe Tsogyel is the principal consort of Padmasambhava. Tradition has it that she is particularly associated with the practice of Vajrakilya and that Padmasambhava taught her and many other dakini’s the Khandro Nyingtik. Some sources say she was first a consort of the king Trisong Detsen who then gave her to Padmasambhava as a mandala offering during an empowerment and later in her life she herself took two consorts of her own. As such she is the ideal of the accomplished female practitioner. At her death she travelled through the sky to join Padmasambhava on the Copper-coloured Mountain in the pure land of Zangdokpalri where he now dwells. She is considered to be the dakini Vajravarahi in human form and an emanation of Tara and the consort of the wisdom buddha Akshobhya.

It is possible that the figure of Yeshe Tsogyel is based upon an aristocrat named Kharchen Za Tsogyel who is mentioned in one of the earliest records, the Testament of Ba, written perhaps in the ninth-tenth century. In this she is listed as a wife of the king and that due to her commitment to meditation she left no children. While this mention may be a later insertion what is certain is that she takes a central place in Nyangrel Nyima Ozer’s Copper Palace, written in the late twelfth century. She is credited as the source of this terma which is the first extensive biography of Padmasambhava. It recalls how the precious guru took Yeshe Tsogyel as his consort when she was sixteen years old to practice in the caves at Samye Chimpu. Here he initiated her into the practice of Vajrakila and through her practice she obtained the yogic power of ‘non-forgetting’ that enabled her to remember all the teachings she had received and place them in a terma for future generations.

This account was then followed by further termas filling in more details. The fourteenth century tertön Orgyen Lingpa discovers the Padma Chronicles which presents a history of Padmasambhava written by Yeshe Tsogyel. A second fourteenth century tertön, Drime Kunga, perhaps based on an earlier account, provides a long story that tells how Yeshe Tsogyel has to struggle to free herself from unwanted suiters and embrace the contemplative life. And in the seventeenth century, Taksham Nuden Dorje in The Life and Liberation of Padmasambhava recounts how, divine from birth, Yeshe Tsogyel was recognised as a special child. However, after two ministers violently compete for her, the king Trisong Detsen takes her for himself. Now as the Queen she meets Padmasambhava, receives teachings and becomes his consort. This scandalises everyone and the king is forced to exile them and this begins their extensive travels and practicing in many different locations. Finally, in an unusual reversal of gender role and display of female agency, she herself takes two consorts - in Nepal a slave called Atsara Saley, and a Tibetan boy called Dudul Pawo. This is backed up elsewhere by Padmasambhava declaring that not only are women just as able to achieve realisation but, “a female body is actually superior”.

Ekajati - Tib. Ralchikma

Ekajati is an extremely fierce female protector, a dharmapali, of the Nyingma Inner Tantras, Dzogchen and terma teachings. She is also found in the later New Translation, Sarma, schools. Her name, Ekajati, means ‘single twisted lock of hair’ and the theme of oneness in her representation points to her as a personification of non-dual awareness - the ultimate protection.

A fully realised being herself, as well as protecting the teachings and those who practice them, she is Queen of the Mamos, wrathful female beings who when outraged cause enormous trouble but when appealed to can support realisation. She also is the guardian of sacred lands and places of power, she develops what is positive and pacifies the negative and when supplicated she may fulfil all our wishes. One role particularly of assisting those that hold the teachings is illustrated by the story of her relationship with the great Nyingma master, Longchenpa. The account goes that Ekajati supervised his performance of the Vima Nyingtik empowerment. Extremely picky, she controlled every detail until he got it just right including copying her precise way of singing in a high strange voice. When he succeeded she danced for joy, proclaiming the approval of his correct pronunciation by Guru Rinpoche and all the dakini’s in attendance.

Ekajati takes many forms, she is portrayed with a variety of heads, arms and legs and holding in her hands a large selection of weapons and other objects. One form, perhaps best known, is along with her single braid a single eye that gazes into the basic space of awareness, a single fang that pierces obstacles and a single breast that nourishes practitioners with non-dual wisdom. Extremely wrathful in appearance she is dark blue or brown in colour and dances naked upon the prostrate corpse of ignorance within the flaming and smoke filled precinct of a triangular mandala. For adornment she wears upon her head a skull crown representing the five wisdoms, a cloth of white smoke around her shoulders, a yogini’s tiger skin around her waist and garlands of snakes and severed human heads around her neck. In her right hand she brandishes the impaled corpse of a samaya breaker while in her left a dripping heart. Also from her left pointing forefinger, leap her retinue of a hundred she-wolves. Around her swarm hoards of raging Mamos. Variations on this include hair that scatters scorpions, a sapphire Swastika representing the mind teachings of Samantabhadra and a ruby lasso representing her power and ferocious activity. She also sometimes has a turquoise curl right in the centre of her forehead.

Found in both Buddhism and Hinduism accounts of Ekajati’s origins and characteristics differ. As a Mamo she can be traced back to Hinduism where these ‘mother’ spirits, as embodiments of the natural world, preside over life and death. Other accounts suggest she is originally a Bon goddess who was introduced into the Buddhist university of Nalanda by the siddha Nagarjuna during the seventh century. And again she is associated with the goddess of compassion Tara. Whatever the truth, the presence of a figure like Ekajati could cause us to hesitate and wonder how we are to understand her. If we are not to take her literally - that Ekajati exists somewhere, looking as she does and exercising her role - then is the only alternative that we dismiss her as another example of local cultural baggage attached to the Dharma? The traditional explanation for the many different forms she takes is that these are how she manifested in the moment that she was perceived by the person who supplicated her. As such each form is conditioned by the individual perception - and limitations - of the practitioner. This idea immediately returns us to the centre ground of Buddhist teaching. Everything we perceive is coloured by our karma - but that does not mean that there is not some sort of reality beyond that perception. Applying this insight here would then suggest that while the form and characteristics of Ekajati - and every other Dharma protector as well - are culturally determined, this does not mean that we cannot appeal for help and that this help will not be forthcoming. And also that when we damage the Dharma for ourselves in some way this does not have consequences.

The Troma Tantra found in the Vima Nyingtik focuses on the practice of Ekajati.

Part Two - What's What in the Great Perfection

Buddha Shakyamuni

Samantabhadra

Garab Dorje

Nyak Jnanakumara

Refuge

Taking refuge is the formal recognition of our entry into the Dharma, it represents having faith in the path and making a commitment. Usually this happens when our teacher gives us refuge during a small ceremony in which we request refuge and in exchange for a clipping of hair receive our refuge name. This may or may not be witnessed by our Sangha - the community of practitioners.

Refuge is also part of our daily prayers.

-

We start our practice by taking refuge in the Outer Refuge of the Three Jewels, Buddha, Dharma and Sangha, the teacher, teachings and community.

-

Within the Vajrayana we also take refuge in the Inner Refuge of the Three Roots, Guru, Deva and Dakini, who are the embodiment of awakened mind, our yogic accomplishments and the expression of these accomplishments.

-

Also within Vajrayana, the Secret Refuge of bodhichitta, the natural state, realised through the subtle body practices concerning the channels, winds and essences - tsa, lung, tiglé.

-

Specifically within Dzogchen we take the Ultimate Refuge which is in the nature of mind, the inseparable unity of the dharmakaya that is empty essence, the sambhogakaya that is clarity and the nirmanakaya that is the unimpeded expanse of compassion.

Refuge may seem a small thing at first but ultimately it is profound. It represents the growing realisation that we cannot find satisfaction in samsara and the decision to put all our energy into something that can bring real happiness for ourselves and others.

Root Guru - tsawé lama

Our principal or main teacher. In the context of Dzogchen the root guru is the teacher who points out the nature of mind and supports us in the practice. With this teacher we have an unbreakable connection. This teacher need not be a rinpoche nor the lama with whom we initially took refuge.

See: Guru Yoga

Refuge

Samaya

Rigpa - Skt. vidyā, pristine awareness

Probably the most important term in the whole Dzogchen tradition. In every day use the Tibetan word rigpa simply means knowledge or intelligence but within the context of Dzogchen this changes to a non-dual awareness that knows itself as the indivisability of emptiness and clarity. Books on Dzogchen translate rigpa in many ways, sometimes using instant presence or pure presence, or alternatively sheer, intrinsic, pristine, immediate or naked awareness. Other translations include wakefulness or even gnosis.....

Nyingma - School of the Ancients

The Nyingma tradition is the oldest of the four principal schools of Tibetan Buddhism. The name, Nyingma, means ancient and it traces its origins to the late eighth century and the first comprehensive spreading of the Dharma in Tibet. Nyingmapa’s have their own canon of teachings organised within their nine vehicle system. Principal amongst these is Dzogchen - a teaching handed down person to person over the centuries and later revealed in treasure texts, termas and also from within pure visions, da nang. The Nyingma Dzogchen teaching is the only Buddhist teaching that is shared by a (nominally) non-Buddhist tradition, the indigenous religion of Tibet, Bön, that has a parallel Dzogchen tradition of its own. Nyingmapa’s emphasise practice over theory although there have been many distinguished Nyingma scholars. The Nyingmapa’s came late to monasticism, the majority of their monasteries only being built during the seventeenth century. And they have generally been disinterested in directly holding political power, having no central authority nor head of the lineage until very recently.

Tradition has it that ......

Kagyé - The Eight Great Sadhana Teachings

The Eight Great Sadhana Teachings are the eight Vajrayana practices found in the Mahayoga Tantra that were according to tradition brought to Tibet by Padmasambhava in the late eighth century during the first dissemination of the Dharma. They consist of five wisdom deities representing the awakened body, speech and mind, qualities and activities. And three worldly deities representing the use of wrathful mantras, the achievement of mundane aims and the controversial practice of ‘calling and dispatching’ that was enthusiastically embraced by later Tibetan sorcerers. An example of this may be found in the biography of Padmasambhava’s student Nyak Jnanakumara who used these worldly practices to get revenge against those that had harmed him. Tradition has it that Vimalamitra then asked him, “Now you can kill by the power of sorcery, but I wonder, can you revive by the power of reality?”.

Primordial Purity and Spontaneous Presence

- kadak and lhündrup

The ground in Dzogchen is the unity of emptiness and clarity. Emptiness is described as being primordially pure, kadak, and clarity as spontaneously present, lhündrup. This means that emptiness has always been free from defilements and that it is clarity out of which - or within - all the phenomena of samsara and nirvana spontaneously arise and self-liberate.

Within the Dzogchen secret instruction series primordial purity refers to the empty essence, the dharmakaya, that is realised through the cutting through practices of trekchö. Spontaneous presence refers to the expression of the dharmakaya in the two form kayas, the sambhogakaya and nirmanakaya, and is realised through the leap over practices of tögal......